by William Kennedy

It's a pleasant autumn afternoon in Sapporo. The stereo plays quietly in the background, in your office there's the quiet buzz of things being done. Looking out the window, you are struck by the wish to feel the warmth of the sunshine and the edge in the light breeze. You open the window -- and the music disappears, activity comes to a halt, the sunshine and the breeze are forgotten. All you can think about is the din pouring in through your window. Welcome to life in the city.

Like crowds and garbage, noise is an unfortunate part of city life and Sapporo is no different than any other city anywhere in the world. It can be argued that for a city of almost 2 million people, Sapporoites have relatively little to complain about and city officials are quick to point out that the public is rarely subjected to excessive noise.

But this by-the-book argument ignores a growing worldwide concern over urban noise. It may also not be the best policy for a city that prides itself on its livability and which lives and dies by tourism.

According to the City of Sapporo, complaints about noise greatly outnumber those about any other kind of pollution. Tetsuo Senshu of the city's Environmental Department says that complaints -- all complaints -- are taken seriously.

"Whenever there is a complaint, we send someone out. We take measurements and tell the complainant if the level is bearable," he says. Senshu spoke with Xene because his boss with whom the interview had been scheduled had been called out to investigate a complaint.

Noise standards in Sapporo are roughly the same as those around the world. The magic number for exposure is 85 decibels for eight hours. Senshu's department uses a new system, LEQ, a calculation which considers maximum and mean levels and duration.

Decibel levels range from 0 to 140. A normal conversation would register about 58 or 60 dbs. Hearing can be damaged from prolonged exposure to 85 dbs and above. In rough measurements conducted by Xene, a pachinko parlor in Susukino was found to have an average level of between 85 and 90 dbs. The maximum level for the parlor was 100 dbs, which is 32 times as destructive to hearing as 85 dbs.

When noise standards are broken, says Senshu, the department will offer "instruction", gentle suggestions that are intended to be regarded as orders. If there is no change, a formal warning is issued, with the threat of a court appearance down the road. Most offenders, he says, are cooperative.

But what of those who are not cooperative or who ignore or flout regulations? Two obvious -- and obnoxious -- examples in Japan are the motorcycle-riding bosozoku and the amplifier-laden trucks known as uyoku driven by local right-wing extremists. Here Senshu acknowledges one of the common problems in enforcing noise standards: jurisdiction. The police, he says, are responsible for both the bosozoku and the uyoku.

The police, however, appear to be ineffectual in dealing with both groups. Comical low-speed chases involving police cars and masked bosozoku winding through downtown streets are common across Japan and the right-wingers seem able to act with impunity. Senshu knows of five arrests the police have made for noise violations by uyoku trucks. The same offender has been arrested each time, he says.

Another problem may be that the noise which bothers you is not noise in the eyes of the city. Senshu says most complaints do not break regulations and therefore require no enforcement, although he says the city will sometimes request a "favor" of an offending party.

For the individual this means that unless you live next door to New Chitose Airport or the rock band Glay have included your balcony on their next tour, you're out of luck.

This policy also ignores a growing worldwide trend which considers environmental noise to be more than just an annoyance. Physicians, bureaucrats and activists in the West have begun to consider the effects of noise on quality of life, stress and even learning among children.

A green paper prepared by the European Union calls noise one of the continent's main local environmental problems. With tongue only slightly in cheek, a report by the city of Vancouver, Canada, two years ago referred to noise as the "silent" environmental issue of the '90s.

In Japan, however, there is still a great division between what is referred to as "medical" and "sense" problems, with attention limited to "medical" issues, particularly regarding hearing loss, industry and airports.

Senshu is familiar with some of the recent research, but remains noncommittal on the dangers of environmental noise; the responsibility, he says, rests with Japan's lawmakers.

"The government should draw the line about whether this (environmental noise) is a medical problem or a sense problem," he says.

Senshu does agree that Sapporo is becoming noisier. He winces at the mention of the high-pitched advertisements for shopping arcades, conversation schools and sports newspapers that are blasted through the city's streets. As irritating as they may be, however, they come nowhere near cracking the noise barrier and so are officially no problem.

In other departments, attitudes towards noise complaints are at best indifferent and border on hostile. Residents complaining to the city's traffic and environment department about situations near their homes are told that they shouldn't have moved there in the first place. For decades, the official position favored the vague all-encompassing concept of "public welfare" over the suffering of individual citizens.

In the last several years changes have begun to creep in. In 1995 the government lost a 20-year legal battle over noise and air pollution on national roads. Tokyo was found to be responsible and was ordered to pay compensation for damages.

Such cases, however, are still rare. There are no lawyers in Sapporo who handle noise complaints and, rather than seeking a solution, people are usually advised to seek financial assistance to install double-pane windows and then put up with the noise.

Concerns over noise pollution have been slow to receive attention around the world it is unlikely to think that Japan, where phrases like gaman (perseverance) and sho ga nai (it can't be helped) are regularly heard, will be a leader in this area. Within Japan, however, Sapporo, whose quality of life is the envy of the country, is well suited to show the way.

Until that happens, though, your only hope is to grin and bear it. And keep the windows closed.

Cash from Trash - There's gold in that gomi - (Aug. 1999)

by William Kennedy

Garbage.

Refuse. Gomi. Whatever you may call it, any foreigner who has been in Japan

long enough to shake the jet lag can be expected to have an opinion about

waste in this country. Whatever these opinions may be, most foreigners --

and more Japanese than you might expect -- can also be sure to have a few

items at home that have been snatched up in late-night "gomi station" raids.

Garbage.

Refuse. Gomi. Whatever you may call it, any foreigner who has been in Japan

long enough to shake the jet lag can be expected to have an opinion about

waste in this country. Whatever these opinions may be, most foreigners --

and more Japanese than you might expect -- can also be sure to have a few

items at home that have been snatched up in late-night "gomi station" raids.One Sapporo resident, however, has taken things a step further, proving that one man's trash is another's cash.

In eight years, Michael Gordon has created a healthy business selling discarded merchandise from Japan around the world. He has sold everything from radios to tires to cars, to as far away as the United Kingdom. As a result, he will leave Japan next year with a bank account and experiences much different than those of the average departing foreigner.

It is somehow natural that Gordon should have a rich, varied background to match his business. The 50-year-old Australian speaks in a tough-to-place accent that seems to roam the globe over the course of a conversation.

Though born and raised in Australia, he spent most of his adult life -- 23 years -- in the United States, in Philadelphia, and only managed to return to Oz at the age of 35. The result is an accent that is sometimes Melbourne, sometimes Philly, depending on the subject at hand.

Something of a jack of all trades, his jobs back home included dynamiting in the gold fields of Western Australia, an occupation he describes as being little more than a glamorized laborer. In a bit of foreshadowing, just before leaving for Japan he spent some time fixing and reselling used washing machines. Though it is tempting to imagine that this prepared him for his future business in gomi, he insists that it was just a one-off way to make ends meet.

His customers included a young couple who had just returned to Australia after a two-year stay in Japan. They convinced him to forego Tokyo for Sapporo. "They told me, 'If you don't have any money and you don't know anybody and you don't have a job lined up, you should head to Sapporo.' And I thought, 'Hey, that's me.'"

After arriving in Sapporo, the progression from full-time English teacher to gomi entrepreneur came about almost by accident. It was, says Gordon, a simple case of supply meeting demand meeting opportunity. The supply could be readily found in any of the city's teeming gomi stations, particularly on the days immediately preceding sodai gomi (bulky trash) pickup day. Prior to the City of Sapporo's establishment two years ago of a ticket system for bulky refuse, the days leading up to the monthly sodai gomi day saw street corners taking on the appearance of outdoor appliance warehouses.

With a seemingly inexhaustible supply, the next step was finding the demand. A stint in the merchant marine had left Gordon with a love of ports and the atmosphere around them. After several months in Sapporo, he paid a visit to Otaru, Hokkaido's major port, and there stumbled across the demand.

Strolling through the port, he came across a large collection of weather-beaten ships that appeared to have seen better days.

"Somehow people transported things in these ships," he says. "It turned out to be the Russian fishing fleet."

Despite having spent so many years in Cold-War America, Gordon had actually always had he calls a soft spot for Russians. His parents were Polish Jews and when Poland was split between Germany and the Soviet Union in 1939, they found themselves in the USSR. Spending World War II under Stalin rather than Hitler saved their lives.

Gordon remembers being in the throes of culture shock and was eager to meet other foreigners. "The Russians helped soften the bumps of being in Japan," he says.

The purchase of a small truck a few months later brought everything together. "Here was the gomi, the truck and the Russians," he says. He loaded up his truck with appliances, headed out to Otaru and was an immediate hit among the Russian sailors.

"You drive out there (to the port) in a truck full of stuff and they knew right away you weren't sightseeing," he says. The first word he learned in Russian was "Skolka", which means, "How much?"

Pretty soon, he had a thriving side business, with his Russian customers happily taking as much as he could provide. The going rates included \2,000 to \3,000 for a washing machine, \3,000 to \5,000 for a stereo and \3,000 to \8,000 for a refrigerator.

Though Gordon may have been selling gomi, it wasn't trash. Many of the appliances he had were trade-ins discarded by electronics stores and he took pains to ensure that everything was in working order. While living in his first apartment in Sapporo, he used to run an extension cord out of his third-story window down to where he had the truck parked beside the building, full of appliances waiting to be tested.

"I often wondered what people were thinking, this cord running down the wall and there I was with all these refrigerators and stereos," he says. When the business was in full swing, he wound up renting storage space in Teine.

The cars came later. Right from the beginning, the sailors would ask Gordon why he didn't have any cars for sale and, after two and a half years of steadily building his gomi business, he was, in his words, "sucked into the car vortex."

From purchasing through shipping and finally sales, the used auto business required an enormous time commitment, and he soon found himself choosing cars over gomi. Like the appliances, the cars Gordon sold were trade ins. Many were misfits: Toyotas which had found their way onto Nissan lots and vice-versa. As with the appliances, he had access to quality merchandise, thanks to the traditional Japanese preference for new over old.

He also benefited from Japan's labyrinthian car inspection system, which actually manages to make buying a new car cost-effective.

"This country is the world's largest repository of good used cars, especially for cars that are six to 12 years old," he says.

Russia's economic woes forced him to find new markets. Car lots in Vladivostok, he says, are full of cars and the current buyer's market there allows canny shoppers to strike their own deals in rubles, rather than yen or American dollars. Instead, Gordon now ships cars to Australian, New Zealand and even the United Kingdom. He usually sends out six to eight cars a month, and the business hinges on the differing vehicle depreciation rates in Japan and elsewhere.

After eight years in Japan, Gordon is looking to return to Melbourne next spring with his wife, Kyoko. He plans to remain in the car business, however, and will concentrate on selling the cars that his agents will continue to buy for him here in Sapporo.

Despite the changes in his business, Gordon still has a particular fondness for his original customers, the Russian sailors in Otaru. He keeps a book listing some 70 different Russian ships, with the names of people he's dealt with on each vessel.

"It soon started to be a social thing as well as business," he says, remembering the warm hospitality he has enjoyed on the ships.

A sailor's life is not easy, and Gordon quietly speaks of the Russians he knows who have died, sometimes in a ship sinking only weeks after he has seen them, other times through accident or misadventure. He has seen friends in drunken violent fights with one another and others slowly killing themselves through alcohol.

Many foreigners are very vocal in their criticisms of waste in Japan and the preference for new things which leads to a massive turnover. Gordon, however, prefers to look at the bigger picture. He points out that constant dumping of goods for newer items helps drive Japan's consumer goods industry. The money that is generated in Japan is then used to purchase other goods, including such things as soy beans from America and wool from Australia.

"The so-called wasteful habits of the Japanese are supporting agriculture and industry around the world," he says.

In the mean time, gomi remains a fact in Japan and as long as it does, there will be people like Michael Gordon proving the value to be found in what is not wanted.

A Face in the Crowd

- Hokkaido's Invisible Escapees from the South - (June 1999)

by William Kennedy

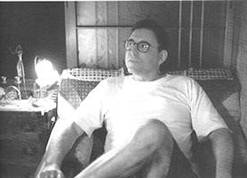

Ken Suzuki is not comfortable talking about how he came to Hokkaido. "What happened to me can happen to anyone," he says quietly. It is the first thing he says. His discomfort in talking about himself is obvious and he frequently adjusts his glasses and runs his fingers through his short gray hair as he tells his story.

"I'm interested in helping others," he says. "And I want people to know that it can happen to anyone. We are all walking on the edge. It doesn't take much to fall over. It can happen to you; it can happen to anybody."

Suzuki talking about his experience as a johatsu, which literary means evaporating. It is the Japanese term used to the describe people who have left behind all traces of their old lives to start anew elsewhere in Japan.

It is impossible to say how many of Japan's missing person cases are johatsu, but their numbers are thought to be growing as the country's continuing economic malaise produces more casualties. Many of these escapees come to Hokkaido, drawn by the sprawling prefecture's reputation as Japan's frontier, a place full of possibilities where those anxious for a second chance can get a fresh start.

For a foreigner in Japan, it is easy to misunderstand and say that this is simply the same desire which helped settle his or her own country. But according to Suzuki, the johatsu is regarded by many Japanese in a much different light. He is a freak, an anomaly who has defied convention by denying social and familial obligations which endure to this day.

Suzuki has broken no laws, nor has he done anything wrong, at least in a legal sense. But for years he has lived like a criminal, looking over his shoulder, fearful that his past would be uncovered. The penalty for being found out would be the loss of the life he has made for himself and a return to what he calls "death in life."

In spite of this, Suzuki agreed to speak with Xene, in the hope that he can somehow help others going through what he has experienced and do something to ease the stigma attached to johatsu.

A member of a shadowy fraternity with no attendance records, Suzuki admits the difficulty in what he is doing. He does not know who he is speaking to and for his own sake, he cannot let his audience know who he is. Only two people in Hokkaido know his secret and the interview for this story -- in which he has been given a false name -- was conducted at this writer's home rather than in a place where someone might overhear him.

The details of his past life, he says, are not important. He was a successful businessman in Honshu, running his own company, until the collapse of the "Bubble economy" in the early '90s. His company went bankrupt and his marriage fell apart soon after that, ending in divorce. He was soon reduced to working as a day laborer, one of the lowest positions in Japan's economic structure.

Suzuki's life was in tatters and he was in shock. "I was merely existing rather than living," he remembers. Had he not left, he says he would have died.

When he did leave, it was completely unplanned. Waiting at the station for his train to work, he simply got on a different line, one heading north instead of south. He traveled across the country for several weeks, staying with friends. When the time came to return home, he found himself facing another choice at the train station.

"To me, one way meant death. The other way meant life," he says. His arrival in Hokkaido was equally unplanned. A backpacker directed him to Oshamanbe, at the southern end of the island. He found his way to Sapporo to look for work and from there he quickly went to a small farming town. There was little else in the area other than agriculture and so Suzuki found himself taking up farm work. Lost in despair and nihilism, he kept to himself, and his life consisted of work and gambling away his wages. Alone in his room at night, he would lose himself in thought.

"I thought, wherever I go, whatever I do, I'll be dead, so it won't matter," he says.

During this time, he lived like a fugitive. He shunned all contact for fear of being forced to return to the life he had escaped. He did not have a phone. He avoided large groups in case he was spotted by someone who might know him from down south or recognize him from a missing persons notice. He was terrified of the police. A speeding ticket or any kind of documentation would create an unwanted paper trail.

"I was in hiding; I didn't want to be found by anyone," he says.

This led to a vicious cycle in which he became even more alienated from society, unable to even rent a video or order a pizza.

It was farm work, he says, that saved him. The farmers he worked with had little time for formalities and no interest in where he was from or what he had done. They were won over by his hard work, and they unceremoniously made room for him in their community. Acceptance came gradually, with the farmers matter-of-factly letting him know when there was work to be done. Notes would be left for him on public message boards.

Working the land with people who simply accepted him for who he was gave Suzuki a sense of fulfillment he hadn't known before. As the years passed, the focus of his fears changed. He now began to worry about losing what he had in Hokkaido rather than having to return to Honshu.

He still maintained a low profile, but he knew that to protect the life he had made for himself, he would eventually have to confront his past. He reached a watershed in his third year, when his driver's license expired. He had always loved driving and knew that he would have to deal with the government.

Before that, though, he had to initiate personal contact. He reluctantly wrote a letter to his family and found himself surprised by the power of his mother's love.

"I thought nobody would understand, but my mother tried to understand and she supported me," he says.

Bolstered by his family's support, he has now officially established himself in Hokkaido. This is where he lives and where he belongs, and he bristles at the idea that he should return to Honshu. "The idea that people might want to take me back is an insult," he says.

A complete resolution, however, is impossible. His immediate family are the only ones in Honshu who know where he is. He has not contacted his old friends and has no plans to. Here in Hokkaido, he has no desire to test the bounds of his neighbors' acceptance with the news that he experienced johatsu.

It's not a perfect ending, but it is one Ken Suzuki can live with. He knows that he is better off than many others in his situation who continue to suffer alone. Having been through the worst of it, he offers some advice.

"You need passion," he says. "If you even the slightest amount of passion, there're always a chance."

As for society in general, Suzuki would like to see a little more compassion and acceptance. In a crowd of 300 people -- particularly in Hokkaido -- there is a good chance that there is at least one johatsu, he says. And he has a warning for those who would still judge him and those like him.

Take care and look around you carefully. Don't assume that everything lasts forever."

Good Things Brewing in Hokkaido

- Small Brewers Making a Name in Local Beer Market - (April 1999)

by William Kennedy

With spring finally having arrived in Hokkaido, cherry blossoms cannot be far behind, and with them the hanami parties with their rivers of beer beneath the trees. But, this time, rather than purchase a standard six-pack of the usual suds, why not try something different, like a Hokkaido microbrew.

Where national breweries pride themselves on consistency, microbrew fans prize their beers for their quirks and moods. A beer's flavor can even be changed by how it is poured, they argue.

"Many major beers taste just like the next one," says Toshiaki Kuwabara, the secretary of the Hokkaido Microbrewery Association. "I don't think it's interesting."

Local Pride

He's not alone in his opinion. Chalk it up to the local love of beer and food, a greater willingness to experiment or a simmering dissatisfaction with the south, but in the few years that small-batch beers have been permitted in this country, Hokkaido has emerged as one of the leaders of the fledgling industry, with a presence out of proportion to its population or economic status.

In Europe and North America, microbrews date back more than 20 years and are now well-established local institutions, but until recently efforts in Japan were limited to under-the-table brewing at home. Local businessman (and this month's Xene cover model) Phred Kaufman remembers appearing on a local TV program in 1992, brandishing a bottle of beer brewed in the basement of NHK's Sapporo building and calling for the law to be changed to allow the brewing of beer in small lots.

At the time, the Liquor Tax Law required that brewers produce 2 million liters of beer a year, which limited the field to only the large breweries. Finally, in 1995, after years of considering the issue, the government relented and relaxed the law, dropping the required amount down to 60,000 liters.

The lowering of the amount came as no surprise and aspiring brewers who had spent years preparing were ready. When the changes came through, the beermakers hit the ground running. The first to see the light of day was Echigo in Niigata, which opened in February 1996 and remains one of the nationwide giants of the industry. It was followed three months later by Okhotsk Beer, a brewery based in Kitami. The opening of Okhotsk was the culmination of eight years of preparatory work by company president Takaya Mizumoto.

Hokkaido is now home to more beermakers than banks. There are almost 30 microbrewers in the prefecture, with more expected to come on board this year. Their ranks include old hands and new faces, dilettantes with deep corporate pockets and devotees with thin personal shoestrings.

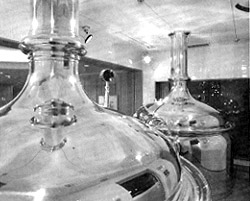

The newest kid on this already crowded block is the Tiffany restaurant in Sapporo's Century Royal Hotel. Beers are brewed on premises and the served up at the restaurant's bar. Kuwabara oversees everything as the bar's master brewer.

Newcomer

Compared to veterans such as Mizumoto or Hajime Sawatari, the director of Otaru's Kairinmaru brewery, Kuwabara is a newcomer. Two years ago, he says, he drank little beer and knew less about it. He got into beermaking through his work in the business development division of Sapporo Kokusai Kanko, which owns the Century Royal. Sapporo Kokusai president Akihiko Fujie was looking for drawing cards to bring more guests and customers into the hotel, and was impressed by the success of the local microbrewers.

"I said, 'Why?'" remembers Kuwabara, "and he said, 'I think we need another business opportunity here.' Three days later, we began an investigation tour."

The tour turned into a year-long odyssey which took him the length of Japan and through Europe and the United States. He visited 183 breweries and sampled more than 570 beers. The year included stints at brewing schools in Osaka and Chicago, but Kuwabara most remembers his 100 days as a trainee at the prestigious Gotemba Kogen brewery in Shizuoka, where he learned the business from the ground up, literally -- he washed floors.

"We kept asking, 'Is this beermaking?'" he says. Funnily enough, it was. He learned the importance of cleanliness and water to brewing, and in time became an expert himself.

When it came time to chose the beers for the hotel, he opted for a pils, a weizen and a dunkel, the three most popular brands for microbrews in Japan. Pils is a clear, light-tasting beer. It is often referred to as pilsner, but, Kuwabara, explaining with the zeal of a new convert, says only beers from the Pilsen region of the Czech Republic can be called pilsners. He compares it to the use of the word champagne to describe only sparkling wines from France's Champagne area.

Weizen, meanwhile, is a lighter wheat-based beer and dunkel is a darker beer with a stronger body. The respective brewing processes for the three range from three weeks for weizen to one month for pils to 50 days for dunkel.

But among microbrews, the variety goes beyond the number of beers on tap. Shunning the preservatives and additives used by the large breweries, microbrewers produce beers whose tastes are influenced by the ingredients used. At the Century Royal, Kuwabara even changes the flavor and body of his beers to suit the seasons.

Sharp Differences

In contrast to Kuwabara's crash-course introduction to beermaking, Hajime Sawatari was one of the microbrewers who spent years preparing for the government's change of mind. His beers for Kairinmaru are the result of years of trial and error. For the past 15 years, he and his

wife Kumiko have owned the popular Fisherman's Harbor restaurant. After making their own wine and sake to go with the seafood, they began working on a beer.

Japan's big brewers have yet to embrace the microbrewers and early on Sawatari got a glimpse of the attitudes he and other local brewers were up against. He thought he had scored a major coup when a brewmaster from one of Japan's major beermakers joined Kairinmaru. Though he had been lured by the chance to be more creative, the brewmaster could not change his ways and soon fell into his old habits about what should and shouldn't be done. The standoff continued until he was let go.

Sawatari is the first to admit he is doing things differently. He and his wife have chosen to go with a completely Japanese operation, with technicians, ingredients and even equipment all found locally. One result is beer that tastes unlike many others. With their sweeter flavor and sharp aftertaste, Kairinmaru's beers are intended to compliment the seafood served at Fisherman's Harbor and at the brewery's own restaurants in Susukino, Odori and Otaru.

"We see it as a 'supporting actor' for the seafood," he says.

Many other microbrews, he says, often taste the same, and some fear the young industry is already in danger of falling into a rut.

"Many of the microbrews, if you can't see them, you can't distinguish one from another," says Sawatari.

He chalks this up to a tendency to rely too much on foreign methods and expertise, particularly German. Many locals brewers, he says, go to Germany to learn the craft, and when they return they then put their operations in the hands of German technicians and brewmasters.

Kaufman also laments the uniformity of the industry. "You look at a lot of microbrews, they've got their dunkels and their weisses," he says.

For contrast, he points to some of the beers he offers, including some made using soba, chocolate and even oregano. Oregano beer, he says with a grin, dates back to the Roman empire, where it was the drink of choice at orgies put on by one of Rome's more successful generals.

What is a Microbrew?

Kaufman and his beers are also at the heart of a controversy over just what can be considered a microbrew. His beers are specially brewed for him by Rogue Ales, a microbrewery in Oregon. He then imports them to Hokkaido through his company, Rothschild Sapporo. The reason for this, he says, is simple economics. As a one-man business, he can't afford to construct his own brewery in Japan.

A Hokkaidoan for 21 years, Kaufman calls Sapporo his home and his beers are only available here, unless they are specifically ordered from elsewhere in Japan. He uses many local ingredients, including hascup, which are sent to Oregon for brewing.

According to the microbrewery association, however, Kaufman's beers are imported and he has been refused admission to the association, which he says denies him much-needed support.

"My beer may be brewed in the US, but I'll be damned if people think I'm bottling Budweiser and trying to pass it off as jibiru(local beer)," he says.

The support the association can offer may one day be vital to Kaufman and many other local brewers. With so many rushing in to join Hokkaido's microbrew boom, some observers fear supply may soon outstrip demand. If this happens, they expect the resulting glut will in turn lead to a shakedown period, in which quality of product and stability will determine the survivors.

Whatever may happen in local brewing circles, however, and whichever companies may live to brew another day, the real winners are Hokkaido beer drinkers, who can savor victory every time they enter a bar.

THEY DO GIVE A DAMN! - Young volunteers help troubled teens - (Feb. 1999)

by Gail Kastning, with Michael O'Connell

Youth. The word conjures glossy images of beautiful young people in red convertibles. Parties. Laughter. Fun without worries or cares. These are the images created by the movie and advertising industries. The impression is simple: young people don't want to think about social problems. Their mandate in life is to have a good time.

Youth Compassion

Kaori Suzuki is a young woman who gives a different impression. This mentor to troubled teens is showing that youth are doing more than generate billions of dollars in sales, that their passion, innovation and energy are prompting great changes in society.

A year and a half ago, a newspaper ad caught Suzuki's eye. It pictured four people playing table tennis and described Sapporo BBS, a group of volunteers who help troubled youths. Suzuki decided not only could she play table tennis, she also could relate to teenagers. Today, she's President of Sapporo BBS.

The organization had its origins fifty years ago, amidst postwar confusion. A group of students from Kyoto had the compassion to do something about the growing problem of urban juvenile delinquency. Many young people throughout the country had lost their parents during World War II and were homeless. Delinquency and moral degeneration were spreading. Realizing the seriousness of the problem, the Kyoto students took action, forming a group called the Kyoto Students' Association for Aid to Juveniles.

The small organization attracted many young volunteers. The goal was to match a volunteer with a troubled teenager to provide friendship, leadership and guidance through one-on-one activities. With the aid of the Ministry of Justice, the organization spread rapidly across the country.

By 1950, it had established itself throughout Japan and, in response to similar youth organizations operating overseas, changed its name to the Big Brothers and Sisters Association (BBS). By 1954, it was decided that the program would aim to assist Volunteer Probation Officers with the rehabilitation of juveniles. Although linked to Japan's justice system, BBS would remain an organization operated by young people to help young people. Since then, BBS has become an integral part of the rehabilitation programs offered by each prefecture's probation offices. The organization is still run by young people, and 27 branches operate in Hokkaido.

Empathy Helps

Kaori Suzuki's desire to get involved grew from her background. When she was a teenager, both parents worked. She was often left alone and felt lonely. Suzuki says she thought of doing something bad like breaking school rules, but she was wise and stayed out of trouble. Now, as a young adult, she can relate to the kids. Her ability to understand how they feel is her main reason for volunteering her time and being involved with the organization.

The work is time consuming but she finds the rewards well worth it. Suzuki feels the smiles, fun and friendships are worth the hours she spends planning and preparing activities. For volunteers, the rewards associated with seeing improvements in the teenagers are definitely reason to become involved in BBS.

Growth and improvement are not, however, restricted to the teenagers. Volunteers also grow and learn from what they do. They improve their management skills and gain experience they wouldn't normally get through their job or at school. They also discover new talents and skills they never knew they had, improve their communication and social skills, and make new friends.

New Challenges

Keiko Tamura, Secretary General of Sapporo BBS, said the group does face some challenges. There's room for improvement in getting out word, she admitted. During the 1960s, Tamura says juvenile crime increased as the Peace Movement spread throughout Japan, and BBS was well-known. However, thirty years later, few people seem aware of the organization. She feels Sapporo BBS needs to publicize itself more actively and to focus on crime prevention. She would like to see the Sapporo branch become more involved in the community and schools.

Tamura also hopes to see more training programs for BBS volunteers. The young volunteers work with teenagers, male and female between the ages of 14 and 19, who have committed crimes or are at risk of committing them. These teenagers lack social skills, some have dropped out of school and many have problems at home. They are referred to BBS by the Probation Office, Family Court, Child Guidance Center, police or schools. Some are on probation or parole, and they are often difficult to work with.

"The juveniles don't even realize they have problems or they don't think they need anyone's help," says Tamura. She adds that the clients have often failed in

relationships with family and friends. They have lost their ability to trust and they can't believe someone wants to take care of them.

Despite the challenging backgrounds of those enrolled in the program, there are few application requirements for volunteers. Applicants need only be between age 18 and 35 and have a desire to help out. Volunteers often feel ill-equipped to deal with the teenagers.

"Working with a juvenile is a huge responsibility and sometimes we have no idea how to solve the problems the juvenile is facing," says Tamura. She believes it is the organization's responsibility to provide training programs to teach volunteers guidance counseling skills, behavior management strategies and activity planning.

More intense preparation may be particularly necessary in light of the increasingly violent nature of Japan's young generation . One-third of all violent crimes in 1997 were committed by people under 20, according to a white paper released by the Management and Coordination

Agency in January. The report blamed increasing materialism and a breakdown of communities.

The compassion that ignited the youth movement fifty years ago in Kyoto may be a remedy. This giving attitude still exists today in the young volunteers at BBS who are proving that young people do care and are willing to volunteer their time to prove it.

THE KANJI AND I (Dec. 1998)

by Mikael Dam

Having lived in Japan for two years, and having spent all of my days and most of my nights in the world of English teaching, I decided to chuck it all and take full-time Japanese study upon myself. It was exactly what I had expected and shockingly different than I thought it would be.

My friend Bill once remarked, upon being forced to hear my laments about my leisurely improvement in Japanese, "What you want is the Japanese Pill." For as long as I have been living in Japan, that was the first time the answer to all my complaints was articulated so clearly. I think we all want that pill, except perhaps for the rare and tortured soul who enjoys studying this infernal writing system and gets off on perfecting the passive voice.

But by and large, we all want it: that one-time substitute for endless hours of Kanji practice (on-yomi and kun-yomi readings included, of course). We want instant relief from having to consider our relation to the addressee when handling complex verbs, and immediate illumination of the elusive wa and ga. Sorry folks, there's no easy way. When undertaking any form of Japanese study, one might as well change one's name to Sisyphus and start rolling that rock up the hill.

Obviously, I'm exaggerating. Think back to the time before you ever entered a classroom or cracked open your first Kanji-a-day notepad. What did you think of Japanese then? If it's your mother tongue I'm ranting about, then think about how you view your own language. Which aspects seemed easy at first, but upon closer examination uncoiled and spat venom in your eyes? Conversely, which stem in this tangled garden looked like it might lead to a Venus fly-trap, but ended up being a welcome chrysanthemum?

Pronunciation and spelling

Let's start with the most forgiving regions of the language. If the only experience you have ever had with Japanese is late-night movies on TV back home, then you might lump Japanese pronunciation together with those of other Asian languages such as Chinese. As you delve deeper, however, it quickly becomes clear that Japanese pronunciation is actually relatively easy. With only a few exceptions, Japanese is pronounced just as it's written. It isn't heavily tonal, like Chinese. In fact, the two sound nothing alike.

Kana spelling, as well, sees none of the silent pitfalls you might encounter in other languages. If you focus singularly on writing things via the kana systems then, small tsu and long u aside, what you hear is what you write. For a language which, on the one hand, includes the most confounding writing system imaginable (more on Kanji later), it is a blessing that everything is spelled with an unchanging syllabary. And though some people still gape in wonderment at the ability to write both hiragana and katakana, the kana are not so hard to learn. Saunter on down to your local bookstore and grab a copy of "Kana Can Be Easy," by Kunihiko Ogawa (Japan Times), the best book ever written on the matter, and the heretofore unintelligible squiggles on the soba shop menu will become well within reach. If only things stayed that simple.

Kanji

This one's entirely up to you. Workbooks, mnemonic dictionaries, practice pads, computer programs, all are ostensibly designed to make your Kanji learning adventure less painful. Don't believe the hype. There's no quick and easy way for the average person to master Kanji. But then again, why should there be? Talk to any Japanese acquaintance and ask how long ago he or she began putting pen to parchment in search of literacy.

It's not a conscious choice in the way it is for all us second- or even third-language learners. Everyone on the archipelago has been doing this since they were in elementary school, so what makes you think you can master it by Christmas? It takes several years of serious study to achieve some proficiency. Consider, though, how much it means to you. Do you need to be able to write your daily journal in Japanese? Do you want to be able to read all the smut that gets dumped in your mailbox? And would it make you sleep better if, rather, than just guessing from the different color of the envelope, you actually knew exactly what that notice from the phone company says? For me and for many of my friends and fellow students, communication is the key. Recognition has it all over production.

The general consensus seems to be that learning how to draw Kanji's component pictures depends on which side of your brain is dominant. You can look at the characters as if they were mathematical equations (man+tree=rest), or surrender to your artistic side (the pictographic approach). Retaining the two or more readings assigned to every character, however, is the real chore. But no matter which way you cut this deck, dealing with Kanji is a chore. As Elisabeth, my cunningly linguistic friend puts it, after the first thousand, it just becomes a pain in the ass.

Grammar

Japanese grammar is an evil coin with two very different faces. In its defense, Japanese is an incredibly consistent language, with a grand total of two irregular verbs. This is the side that has most impressed me. No matter how tied up and frustrated I become within the wicked ropes of Kanji, I always placate myself with the fact that I can easily conjugate on command. Many learners of Japanese have expressed the same sentiments, albeit with such a frightened gleam in their eye that I do believe many of us hold it to be our last chance for a linguistic lifeboat.

The flip side can be rough. While every language has humble and honorific speech, Japanese goes much further that way than most. It is language of particles that seem to disappear in conversation only to reappear on the pages of your textbook. It is an utterly untranslatable language. Amidst screams of horror, I have witnessed many around me come to these realizations. My friend Noriko is a trained teacher of both English and Japanese, and she has a theory for bridging the gap of meaning.

"Recognize what you instinctively want to do with the language, and then do the opposite," she suggests. She's not far off the mark.

What I have also realized is that most foreign speakers of Japanese over-use subjects and particles to a farcical extent. In the classroom I was browbeaten into submission on the point of making complete sentences, but hang around any coffee shop in town and listen to how many watashi's you actually hear. Do yourself a favor and leave that subject by the roadside right now. And while you're at it, barring usage for clarity, ditch the particles. When Japanese friends tell you that you don't need particles to understand Japanese, they do know what they are talking about. Whatever way you choose to study -alone, privately or in a group -consider yourself, in an odd way, lucky: after all, you are in Japan, which is a better place than many to study Japanese.

And though it may sometimes seem that every single thing you say is met with bewildered stares, do not let all the ludicrous theories about the unpenetrable uniqueness of the Japanese language get in the way. The grammar may be bewildering and Kanji torturous, but your effrots are not in vain. Somewhere out there, some little obasan or a drunken sarariman is just waiting to throw a "Jyouzu desune!" your way.