by Carey Paterson

K aoru and Naoki Yamaguchi are the perfect couple. Both hold law degrees

from prestigious Waseda University. He works for a top-tier bank in metro

Tokyo. She has a proud history of volunteerism. The two enjoy a loving,

trusting relationship, and when they hit the ski slopes they blow away

snowboarders half their age. Still, by traditional Japanese standards

their marriage could be considered a failure: The Yamaguchis have chosen

not to have children.

They are not alone. Although "ichi hime ni taro" ("first child a girl,

second a boy") describes the ideal Japanese family, more Japanese marrieds

are choosing a lifestyle of "zero hime, zero taro" (no girlchild, no boychild),

the latest in lifestyle changes that include the decline in the marriage

rate and the rise in women who opt to have children while remaining single.

Although Kaoru does not feel she has to justify what she considers a private

decision, she believes her choice makes sense. She says she has enough

blood relatives and adds, "I do not like children so I felt it would be

a waste of time to raise my own children."

The couple's decision has given them a rare degree of freedom. In addition

to snowboarding, they golf together and have scuba dived among sharks

in the Maldives. "I can do anything I like at any time without consideration

for other family members except my husband," Kaoru says.

FLOUTING TRADITIONS

Despite Japan's declining birthrate, older Japanese consider Kaoru's attitude

selfish. Centuries-old cultural influences still encourage couples to

have children: Shinto is an agrarian religion at heart, where fertility

rites are central, and Confucian thinking invests great importance in

the family and its continuance.

One women in Osaka Prefecture who married and remained childless for a

few years was menaced by middle-aged women in the neighborhood supermarket.

They circled their shopping carts and demanded an explanation. Kaoru says

she is fortunate not to have experienced pressure from friends. Relatives,

however, are a different story.

"My in-laws were meddlesome, asking me when I was going to have a baby

when we were a newly married couple. I did not find any support from anyone,

but I did not need any support, because it is a purely private matter

to have children or not. Everybody insensitively and directly asked me

when I was going to have baby. Recently, I seldom have these kinds of

questions, maybe due to my age." (The Yamaguchis are in their forties.)

She says she is also lucky that her husband's elder brother has children,

which frees her from responsibility for continuing the bloodline. Not

all women are as fortunate or determined, and many who yield to the pressure

later regret it.

"Sometimes I feel only hate for my children," one reluctant mother confided.

Another couple was more ambivalent about their choice not to have children.

Although Jeff and Emi Seward both love kids, they are daunted by the prospect

of being parents and are childless by choice. (Their names in this article

have been changed.)

20 YEARS OF SLAVERY

"Once you have a child, you want to love it," says Jeff, an English teacher

in Sapporo. "It's 20 years of slavery, a full-time job. It just doesn't

fit my indolent lifestyle. With a dog or cat, you can put food in the

bowl for two or three days and leave," he jokes.

Emi earned a degree in economics from a two-year college before launching

her career in advertising. She says she is happy without kids.

"My friend who have children say it's nice to have kids, that I should

have a child. When I hear this I feel, maybe I want a child. But it's

much easier to bear one than to raise one." Besides, Emi says, she is

enjoying life in her thirties more than ever: "I'm satisfied with my life."

In addition to the normal responsibilities of raising children, the Sewards

think it is harder than ever to bring up kids in a Japan of high prices

and social dislocation.

"Children are becoming dangerous," Emi says. "There have been several

incidents recently involving children. People blame the family, but the

cause is not just the family, it's society. The environment now is different

from when we grew up. Children are exposed to many influences. They can

choose from many recreations. This great choice has led them to confusion.

There is not enough guidance."

Jeff agrees: "You leave them in school where the bullies would take care

of them - or they'd become the bullies. I don't see the environment as

worse than America, but it seems that, here, people turn a blind eye when

they see people doing wrong. People blame the parents without confronting

them."

Another reason they have remained childless is age. Jeff is in his mid

forties. Emi, who married him a year ago after her first husband died,

is in her late thirties.

"Women who have children in their forties are fooling themselves," Jeff

says. "They don't want to feel cheated in life," so they have a child

to prove they can have it all. "But they're setting themselves up for

disappointment."

Social commentators also attribute the "zero hime, zero taro" phenomenon to the ongoing reevaluation of priorities. Many men and women in Japan feel cheated by having devoted their whole lives to their families or company, the thinking goes. Their children recognize this and wish to avoid the same mistake.

Jeff believes this is true in the U.S., too: "I did all the relaxing my parents didn't do," he says. Only one of his siblings has children, although he insists they had a happy family life as children.

Many cultures have regarded children as an insurance policy for one's later years. Jeff thinks this attitude no longer makes sense in Japan.

"Even now, kids don't take care of their parents. Usually the parents have more money anyway. I might worry about getting old, but not because I have no children." The time when children were seen as providing security "seems like a different era."

An additional worry for older Japanese is having no-one to visit their grave at memorial anniversaries and the Obon holiday.

"It's not a concern for me," Emi says. "Maybe this is because I'm the middle child. My brother is taking care of my parents and the bloodline will continue through my brother's family. My parents' name will continue. That's one reason I don't get any pressure to have children."

Nosy neighbors and the elderly are not the only ones alarmed by the spate of childless couples. The Japanese government has been struggling to increase the birthrate to soften the brunt of the aging demographic, and companies like Naoki's offer a special bonus for childbirth. Childless marrieds are in a unique position to evaluate efforts to boost the birthrate.

"I think improving women's working conditions is the best way to increase the rate," Kaoru says. "Women don't want to see their working conditions deteriorate after having baby. If the government introduces such a policy as a means of pushing up the rate, I think it will be good for not only the birthrate but also the welfare of women."

Emi agrees: "There were lots of women with kids at my first ad agency job. Seeing them, I thought I could have a child and work. But it depends on the company and its culture."

No-one knows what the future holds for Japan or for couples who forego children, but Kaoru says she is comfortable with her choice.

"So far, I haven't had any trouble living with my decision. I have no regrets."

Internationalization: No Pain, No Gain (June, 2000)

Internationalization in Japan used to be about sister-city affiliations,

student ex-changes and other feel-good activities. Today it is moving

to more anxious grounds.

Earlier this year a Brazilian woman won an anti-discrimination suit against

a shop that refused her entry. Here in Hokkaido, activists have criticized

the exclusion of foreigners from hot springs in Otaru. Some municipalities

have started allowing foreign residents to work in government. The TV

program "Soko ga Hendayo Nihon-jin" (Weird Things about Japanese

People) is showing that people from around the world not only can speak

Japanese but can articulate issues better than many natives do. These

changes show that the focus is shifting from feeling good to doing right.

To these actions, there have been reactions that are opposite if not equal.

Tokyo's populist governor Shintaro Ishihara in April criticized visa overstayers

by suggesting they might riot in an emergency. His words angered many

Koreans and Chinese who believed the governor was turning history on its

head: It was Japanese citizens who rioted against non-Japanese in the

Kanto Earthquake of 1922. A lock manufacturer in March ran advertisements

that played on fears of burglary by foreigners, even though foreigners

commit fewer crimes per capita than do Japanese.

The expression "no pain, no gain" sums up internationalization

in Japan today. The essays that follow are a contribution to this dialogue.

Questionable Questions

By Melissa Reiber

The TV host isn't asking me anything momentous and I'm certainly not saying

anything profound as the video camera whirs. But she doesn't mind, since

the questions are not about her viewers learning anything - except how

I am not like them. Like so many interviews, this one is really an exercise

in highlighting the distinctiveness of Japanese culture.

The sad irony is that such interviews masquerade for kokusai-ka, or "internationalization,"

when they serve the opposite purpose. When one hears the classic distancing

question "Do you like sushi?", the proper answer is a foregone

conclusion: Because you are not Japanese, you can't like sushi; because

we are Japanese, we love it. Not convinced that there is an ongoing quest

to create a gulf between this land and elsewhere? Try to recall the last

time you heard a native ask a foreigner how that person's country is similar

to - not different from - Japan. Or watch the disappointment when you

downplay the differences.

Because so many questions are asked with suspicious motive, there is the

danger of overreacting and treating any unwelcome inquiry as suspect.

But even the most annoying of questions can still adhere to the spirit

of genuine communication.

Take the typical cookie-cutter question, "How long have you been

in Hokkaido?" or "Why did you come to Japan?" As clichˇd

as it may be, it aims for interaction. And if spoken in a second language

it shows a desire to improve communication ability. It can be tedious

to suffer these scripted conversations in succession. But when one realizes

the subtext - true desire for intercultural exchange - it's unfair not

to welcome the effort. English speakers, in particular, complain of being

treated as foreign language speaking machines. However, short of exceptional

demands on one's time, it is unrealistic and uncharitable to shrug off

someone from another culture looking to have a few words.

The ignorant question may seem worse than the sushi inquisition, but this

too can be a genuine kokusai-ka inquiry. "Do they eat tofu in China?",

an unworldly Japanese friend asks. "Do you eat sushi every day?",

my less informed acquaintances back home want to know. Although the answers

should be obvious, the questions are still welcome "quest"-ions,

admirable as legitimate searches for knowledge.

With the rude question, the motive is important. When someone asks how

much money I make, it's hard to know whether this person is just plain

rude to natives and foreigners alike, or is assuming that manners do not

exist beyond Japan's national borders. Only the latter case is distancing.

When the rude question comes simply from narrow-mindedness, there is a

chance to educate the inquirer.

Ah, the ordinary question, sublime in its unremarkableness, indeed, for

its sheer ordinariness. It is kokusai-ka achieved. Directions to the post

office, you ask? What's the time? What nice weather we're having? This

is pure communication that transcends differences in a wonderful banality

of normal human interaction.

Unfortunately, we must return to TV-land, where thrives the dreaded pseudoquestion.

"What Japanese food can't you eat?" beams Ms. TV host, video

camera awaiting signs of revulsion. But I will not play this game. I -

and millions of other people throughout the world - happen to like sushi.

"Mayonnaise," I tell her. "I can't stand it, and it's slathered

on everything here!" Next time, please just ask for directions.

Evaluating Cultures

By Melissa Reiber

This in itself would not be curious, except for two facts. I do not live in a nightlife district. My apartment is in a quiet residential neighborhood where clunky shopping bikes are more the norm than the roaring motorbikes seen downtown. Nightlife here means popping out to the convenience store for instant ramen and a comic book or a less wholesome read.

Hence the second odd aspect of chez Catherine. There are no customers. Absolutely none. In my several years at this apartment, I have seen no signs of life at Sunakku Katoriinu other than the above-mentioned vegetation, three cats and the Japanese matron herself.

At first I wrote it off as one of those things I, as an outsider, couldn't hope to fathom. After all, I'd never noticed the apartment nearby with all those video surveillance cameras, three-car underground garage and protective fencing. It wasn't until my Japanese friend called attention to the bristling security features that I realized it was an underworld stronghold. Sure I knew that my neighborhood is notoriously gangster-infested. But I hadn't given much thought to that apartment or the fact that only the fanciest imported autos parked in front.

This is why I thought I might be missing something obvious with Kate's place that an insider might pick up on. I tried a few theories that took into account cultural aspects. Mama exemplified Japanese dedication to work, the ganbaru kokoro (fighting spirit). She was the embodiment of gaman (perseverance) in the face of total indifference by would-be patrons and any absence of business success. This got me nowhere.

The foreigner prone to conspiracy theories imagines something more sociologically sinister, that the shop is really a front for the nefarious activities rife in Japan. Seen through this Crichtonesque mindset, it's obvious that she's running a gambling den or money laundering operation - or maybe even sequestering those NHK-TV money collectors who come calling. It's just that no-one except her enters or leaves by the front, back or windows, thus ruling out these possibilities. Besides, the real gambling den, a mahjong parlor just around the corner, operates in complete openness. No need for subterfuge.

My Japanese friends advance a few theories of their own: That mama has been set up in business by a former lover. (Mama is staying open to show her sweetheart her devotion when he returns.) That she's just a lonely soul making busy work for herself in a novel way that perhaps fulfills some longstanding fantasy. That she's running a bouri baa (clip joint), although the only things to clip are her cats' claws. That she's some kind of chukai (intermediary) for drugs or prostitution or phone sex, although again, the absence of customers and the fact that she's never on the phone and never absent from her duties undermines that theory. "Anyway, she's waiting for someone," a friend insisted. "Who, I don't know."

At first mama's perpetually nasty stare made me want to retaliate. I thought of asking her about her business: "Slow night tonight, huh Kate?" I even considered patronizing her establishment just to get to the bottom of things. With me as her best customer - her only customer - she'd have to tell me. But I worried she'd try to make up for years of zero income by sticking me with a ridiculous bill.

I asked my garrulous neighbor for her take. "Strange, isn't it?", were her only thoughts. The fact is, I have no better or worse idea what mama's story is than my native friends do.

My best guess now is that it would be better not to see mama through the prism of some exotic Japanese value system. The leading theory is that she represents a more universal type: the nutty eccentric. Mama then becomes a Far Eastern femme fatale, a figure of pathos straight out of Billy Wilder's "Sunset Boulevard," an aging Gloria Swanson unable to face the fact that her fans are gone, her looks are gone and her life is the theatrical production of a mind out of touch. Listen closely and you may hear her say, "I'm ready for my close-up, Mr. Kurosawa."

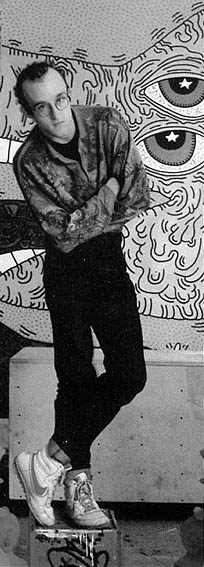

Seeing Haring (April, 2000)

by Carey Paterson

If any artist owned New York in the '80s it was Keith Haring. His faceless dancing figures, bursting with energy and iconic simplicity, were to art what Donna Karan was to fashion in the '90s. No sidewalk market was complete without a shirt or button featuring a Haring design.

An exhibition at Sapporo Art Park, from April 1 to May 21, will showcase Haring's trademark line-paintings and introduce his explorations in other media, such as print making and sculpture. Among the 80 paintings are one that is more than six meters wide and others on plastic sheets and coffee cups. Documentary photos and films will explore the artist's life and thought.

The show covers the period from 1978, when he was a student at the School of Visual Arts in New York, to his death in 1990.

Haring is best known for his cartoonish figures composed of uniformly thick curves. Barking dogs, dancing people, floating UFOs -- these are all elements of his iconic vocabulary. His world combines the mystery, immediacy and wonder of aboriginal art with an awareness of modern social issues.

Haring was born in 1958 and grew up in Pennsylvania. His parents encouraged his artistic aspirations, and after high school he enrolled in the Ivy School of Professional Art in Pittsburgh. He quit after seeing demoralized commercial artists.

"I quickly realized I didn't want to be an illustrator or a graphic designer," he writes. "The people I met who were doing it seemed really unhappy; they said they were only doing it for a job while they did their own art on the side, but in reality that was never the case -- their own art was lost."

After showing his work at the Pittsburgh Art Center, Haring enrolled at the School of Visual Arts in New York as a scholarship student.

Upon arriving, he was impressed by New York graffiti. He admired its rawness and spontaneity, and it was his early chalk drawings on the New York subway that launched his rise to fame.

"One day, riding the subway, I saw this empty black panel where an advertisement was supposed to go," he wrote in his diary. "I immediately realized that this was the perfect place to draw. I went back above ground to a card shop and bought a box of white chalk, went back down and did a drawing on it. It was perfect -- soft black paper; chalk drew on it really easily. I kept seeing more and more of these spaces, and I drew on them whenever I saw one. Because they were so fragile, people left them alone and respected them; they didn't rub them out or try to mess them up. It gave them this power."

Almost overnight, his below-ground works gained an underground following, and respect turned to acquisitiveness: "By 1984... everyone was stealing the pieces. I'd go down and draw in the subway, and two hours later every piece would be gone. They were turning up for sale."

Although Haring has been called a graffiti artist, he never defaced trains and his work was meant to include elements of performance. It was interactive, and part of the meaning was in his contact with the passers-by who scolded him or expressed curiosity.

His work also is more varied than many people believe, as anyone knows who has seen his intricate surface patterns. The Art Park show is important in highlighting just how wide-ranging is his contribution to contemporary art.

In many ways Haring epitomized New York's go-go '80s. By the time he turned 25, Haring's chalk drawings had made him a celebrity. This was just when Wall Street traders barely out of college were making millions in minutes. These financial experts were products of the Ivy League but they were turning the rules of finance on their head. In the same way, Haring was a product of the art school system but his appeal was subversive: it went directly to the public, largely bypassing the usual path of gallery showing and critical approval.

"I think that in a way some [critics] are insulted because I didn't need them," he writes. "Even [with] the subway drawings I didn't go through any of the 'proper channels' and succeeded in going directly to the public."

His death was also emblematic of gay activism in New York in the '80s precipitated by the rise of AIDS. Haring, who was gay, was diagnosed with the disease in 1988 and died two years later. Since then, the artist himself has become an icon to the cause of gay activism.The exhibition will run from April 1 to May 21. Admission is \900 for adults, \450 for high school and college students, \180 for elementary and junior high school students. Groups of 20 or more will receive a discount. Contact: 011-591-0090.

The Magnificent Leaven - Bagelmeisters Bring Internationalization -

(April, 2000)

by Carey Paterson

Yvan Chartrand had just one gripe about his new home in rural Hokkaido: He couldn't find decent bread. Not one to go without, the Canadian baked his own. Now, the thousands of bagels he makes each week in Sapporo are adding a touch of culinary sophistication to the city.

The bagel is undeniably cosmopolitan, an immigrant's food that marries European mystique to hearty New World promise. It is unique among breads for being boiled before baking. Although the dough includes just a few simple ingredients (flour, water, salt, yeast and sometimes malt), making a great bagel is anything but simple. It is an art developed over four centuries -- as long as the Japanese have been using soy sauce.

Legend dates the bagel's origin to a 17th-century battle in which the king of Poland repelled Turkish invaders. A grateful peasant commemorated the event by creating a stirrup-shaped bread in honor of the equestrian king. Because bagels are round, they came to be considered lucky: People have always imagined circles to have magical powers. At the turn of the 20th century, that luck ran dry for Jews in Eastern Europe. Poverty and pogroms displaced a great number, many of whom settled in New York and Montreal, bringing their baking craft with them. By the middle of the century, prepackaged frozen bagels were widely available in North America.

DESCENT FROM HEAVEN

Chartrand says his hometown of Montreal, with its large Jewish population, is a bagel heaven. The baker studied ecological agriculture at McGill University in Canada, and worked at a hospice for the handicapped where he met his wife. He later followed her to Nakashibetsu, Hokkaido, near her hometown, where they lived for six years before moving to Sapporo in 1998.

Although he appreciated rural Hokkaido, Chartrand still longed for the bread he was raised on. Out of frustration, he started baking at home. Later, he worried that his French and English teaching experience would not be marketable back in Canada. He decided to change careers, opening Bonjour Bakery two years ago in Sumikawa, where he makes bagels and other breads. He sees his shop as a holdout against a mass production system that encourages mediocrity.

"When you go to a department store there are two kinds of bread," Chartrand explains. "You have bread made from frozen dough; it's not made there. The other kind of bread is premix, where all the ingredients -- milk, yeast -- except the flour are put together. All you do is add water, let it rise, and bake it. You don't need to be a baker, you just follow the recipe." Because these doughs are not used immediately after mixing, they include eight to 10 chemical additives to enhance rising, he warns.

"One customer came in and told me she saw a baker spraying down the bread right in front of her. He was using an anti-mold spray. You'll find that in the States, too. If they do that in front of the customer, imagine what else they do!"

Chartrand's old-fashioned approach has earned him interviews on TV, and has drawn competitors to his doors. "My wife's getting good at spotting them," he says. "They ask about the flour. She asks, 'Are you a baker?' and they usually admit it. Of course, if I owned a sushi shop in Canada, I'd go and look [at other shops] too."

TRADITIONS, INNOVATIONS

Tokeiday, Sapporo's Western-style clock tower, is a monument to internationalization,

a reminder of the foreign experts who played a decisive role in Hokkaido's

early development. Immediately north of Tokeidai is a newer testament

to internationalization: M's Bagels, a sandwich shop that opened in 1998.

Proprietor Hitoshi Moriya left his job in the travel industry to launch

the shop. He calls bagels "the ultimate... It only took one to satisfy

me," he reminisces of his first taste, in Vancouver, Canada.

Bagels are particularly popular with health-conscious women in their twenties

and thirties, according to Moriya. "This is probably because of their

interest in watching their weight. At the request of my customers, I've

indicated how many calories are in my various sandwiches."

Moriya has kept some bagel-making traditions and dispensed with others.

Unlike purists, he doesn't boil his bagels.

"I started out boiling them. After I got some favorable comments

on ones I'd steamed, I began steaming them all." And he uses Hokkaido

flour, whose lower gluten content than North American flour makes for

a slightly less chewy texture.

Although he enjoys the denser standard bagel, Moriya suspects his customers

will say they are too hard if he makes them that heavy. But he uses traditional

ingredients. "Recently, some makers seem to be using sugar and egg,"

he notes. "I never do that."

Chartrand makes fewer concessions to local tastes. "I try to give

customers the same bread I would eat in Montreal," he insists. "It

took me at least a year of trial and error before I was happy." He

boils his bagels, and uses Canadian flour for maximum chewiness. Additives?

"There's none of that stuff," he says. "About 75 percent

of my customers are between 40 and 60 years old. They tell me the bread

tastes like 'mukashi no agi,' or "bread from the good old days."

Although priding himself on authenticity, he admits that even North American

bagels are not completely traditional: bagels were first made of sourdough,

not with the dry yeast that is common today. Dry yeast baking is a relatively

new baking method. He also has experimented with exotic flavors including

chlorela, a chloryphyl-rich alga, and buckwheat.

The final test is taste. "If you want to know a good bagel, the first

thing is to cut it in half then smell it. It should smell like bread.

I did it with another bagel and I swear it smelled like Chanel No. 5.

It should also spring back [when squeezed] and not fall apart." It

should be chewy and "give you the satisfaction of knowing you've

eaten something good in good company."

RENAISSANCE WOMAN

Scuba instructor, clothing saleswoman, aquarium fish-feeder: These are

just a few of the jobs that have taken Hiroko Kawachi from Hokkaido to

Australia, Saipan and the Maldives. She has added bagel cafˇ owner and

hostess bar mamma to her resumˇ, making bagels by day in Kotoni/Hachiken

and small talk by night in Susukino. Moon Salt, her stylish shop, faces

JR Kotoni Station and becomes and open-air cafˇ in summer.

"It was like nothing I'd ever eaten," says Kawachi of her first

bagel, sampled in Los Angeles. She decided to open her own shop and name

it Moon Salt, because "a bagel is shaped like a moon and is made

from only flour, salt and water." Simple it may be, but Kawachi says

it was hard work getting her bagels to taste the way she wanted. She apprenticed

for more than a year in Tokyo under a master known as "Mr. Bagel"

who operates two respected bagelries in Tokyo.

Although she uses imported dough, she is a local booster. "I'd love

to use Hokkaido flour and to make the bagels completely from scratch,"

she says. "Farmers in Hokkaido are working to improve the quality

of their wheat. It's important to use Japanese flour, because I'm Japanese

and I believe you should support your growers."

Kawachi said it was more expensive than she expected to start the shop

two years ago. The Hokkaido Government helped with \8 million under a

program to finance venture businesses.

Chartrand also had help from the prefectural government. He says it was

surprisingly easy to set up the business: "People bent over backward

to help us. The Chamber of Commerce approved our loan request right away."

There was very little red tape, and he was accepted quickly when he marketed

his bread to distributors.

The hardest part was growing the market and scheduling the work. He is

generous in giving his wife credit. "If I'm working 12 hours a day,

my wife is working 16," says the father of three. "It wouldn't

have been possible to have started the business without her."

ORGANIC BREAD

Interest in bagels as a health food may mark a trend toward organic bread,

which excites Chartrand. Unfortunately, he says most of the organic flour

available now has a gluten content too low for bagel-making. As a student

of ecological agriculture, he also feels upset when domestic interests

misrepresent foreign agricultural products.

He accuses flour companies of promoting domestic goods by raising fears

of agricultural chemicals in foreign flour. This is misleading, he believes,

since his flour is 100 percent Canadian, and in Canada it is cold enough

to store wheat without using chemicals. Although his flour is not organic,

he says it has been tested and shows no traces of agricultural chemicals.

He takes this bill of good health seriously. As he says, "With bread,

it's really what's inside."

Judge for yourself

![]() M's Bagels, Chuo-ku, Kita

1-jo Nishi 1-chome, Sapporo

M's Bagels, Chuo-ku, Kita

1-jo Nishi 1-chome, Sapporo

Tokeidai Bldg. B1: A 3-min. walk from Odori Subway Sta.

![]() Moon Salt, Nishi-ku, Hachiken

1-chome Nishi 1-jo 1-1

Moon Salt, Nishi-ku, Hachiken

1-chome Nishi 1-jo 1-1

Arukasaano Kotoni A: A 10-min. walk from Kotoni

Subway Sta., or 10 sec. from JR Kotoni Sta.

4-1: A 10-min. walk from Sumikawa Subway Sta.

Looking Past The Mask

- Hollywood Does a Retake on Japan - (Feb. 1, 1999)

by William Kennedy

Japan is hot. Hey, all of Asia is, come to think of it. No, not that kind of hot. I'm talking about "hey babe, let's do lunch" hot, the kind of hot that gets on magazine covers. Asia is Hollywood's flavor of the week.

By the time you read this, the film Snow Falling On Cedars, about murder, love and the clash of Japanese and American cultures in the 1950s, will be in theaters. Arthur Golden's best-selling novel, Memoirs of a Geisha, is about to become a movie, courtesy of Steven Spielberg, no less. Hong Kong star Chow Yun-Fat is following up his American debut in The Replacement Killers with a non-musical version of Anna and The King, which co-stars serious big-in-Japan actress Jodie Foster. The most-talked about character on Ally McBeal, America's most-talked about TV program, is lawyer Lucy Liu, played by Ling Woo.

So, with all this Asian prominence, we can finally say goodbye to the stereotypes, to the Europeans pretending to be Asian, to the bowing "ah, so" caricatures, to the astonishing ignorance that makes you want to crawl under your seat in the theater. Right?

Xene spoke with a local cinema manager, a visual arts professor and filmmaker, and a film critic, and the general reaction was of guarded optimism. Things are looking good, but Hollywood still has a lot to answer for.

"I think that non-Japanese people still seem to have images of hara-kiri and Fuji-yama when they think of Japanese people," says Atsushi Tsuchida, who handles public relations for the Sugai Cineplex in downtown Sapporo.

Tsuchida is referring to Hollywood's long history of stereotyping and misunderstanding Asians -- particularly Japanese. Since the early days of the film industry, Japanese women have generally been either demure geishas or dragon ladies: doormats or predators. Japanese men, meanwhile, have over the years included repressed sex fiends, vicious Imperial soldiers/yakuza, button-down corporate androids or growling samurai. Most of these characters, both men and women, have been slaves to obligation and duty. The majority have been either villains or patsies.

Tsuchida says many of his audiences are bemused by the stereotypes they find in American movies. "They often laugh bitterly," he says.

In the past, sympathetic, or at least non-negative, Asian characters were often played by heavily made-up Westerners with their eyes taped back. The legion of actors who went "yellow" in Hollywood's "golden" age includes Katherine Hepburn, Peter Lorre, Marlon Brando, Peter Ustinov and Mickey Rooney. Even as recently as 1985, song and dance man Joel Grey played a Korean martial arts instructor.

Tsuchida chalks it up to a racism that Westerners deny and may not even be consciously aware of. "Even though they [Westerners] say there is no prejudice, I think there must be some."

Images of Japanese in Western movies changed with the rise of Japan's "bubble economy" in the 1980s and the release of two American movies: Black Rain and Rising Sun. The Japan of geisha and samurai gave way to another Japan, a decadent, high-tech place of murder and high finance. With this new image came new stereotypes: yakuza and salarymen, foot soldiers in the shadowy service of Japan, Inc. as it strove for world domination.

In Rising Sun, the Japanese despised the West while seeking to take it over. The message: hide your daughters, America, lest they be pressed into service as sushi trays. At the time controversial, Rising Sun is now remembered as unintentionally humorous nonsense which actually played down the anti-Japanese sentiments found in writer Michael Crichton's (yes, that Michael Crichton) 300-odd pages of dodgy research, paranoia and xenophobia.

Black Rain, meanwhile, is a slick tale of a renegade New York policeman (Michael Douglas) and his efforts to track down his partner's killer, an Osaka-based yakuza maverick (Yusaku Matsuda). It is considered a much better film than Rising Sun, but should never be mistaken for a realistic portrayal of modern-day Japan. Director Ridley Scott is famed for flashy, good-looking movies in which substance takes a backseat to form. Think of his work as brain candy.

Ryusuke Ito, an associate professor of visual arts at Hokkaido University of Education Sapporo, says that beneath Black Rain's exotic exterior is a garden-variety cops 'n' robbers story that is almost as old as moving pictures.

Ito, who studied at the Chicago Art Institute and has long been interested in filmmaking, says Japanese were not targeted by the movie's makers. Japan was in the news and provided ready fodder for opportunistic screenwriters.

"It's basically a gangster film, so it doesn't matter whether there are French gangsters or German gangsters. At the time Japan was hot stuff," he says.

Tsuchida, too, confesses a soft spot for Black Rain, particularly because a Japanese actor (Matsuda, in his last role before dying of stomach cancer), had the rare opportunity to play a lead role in a Western movie.

"But, still, he was the villain," he says.

Tsuchida's comment is an example of the general resignation and apathy found among many Japanese viewers regarding how Hollywood chooses to present Japan, the Japanese and those of Japanese descent. A freelance writer who writes on movies for The Hokkaido Shimbun told Xene that the issue is "a minor one," adding that many moviegoers do not think of such things.

The writer, who declined to give her name to Xene, suggested that such matters were better handled by academics in Tokyo.

"There aren't many people who try to learn something from movies," says Tsuchida. "Even though they see Japanese characters presented unfairly, I think that they just think, "Oh well, sho ga nai," and they don't think beyond that."

Ironically, some suggest that it is this reluctance to speak out that has allowed Hollywood to get away with cartoonish portrayals of Asians long after it was called to account for unfair treatment of women, African-Americans, Jews and Arabs, among others.

Part of the problem is that audiences and movie makers in the West have very little contemporary material from which to draw their images of Japan and Japanese. Ito says few movies are made in this country now and even fewer get exposure overseas.

He says this is because, under the current system in Japan, many movie studios such as Toho have found it more profitable not to make movies, but instead to concentrate on distribution. Today's crop of movies are being made by young filmmakers who are bankrolled by businessmen looking for tax hedges. Free from concerns about accessibility and box-office earnings, these directors often make dense, intensely personal films that garner awards and accolades at international film festivals but have trouble finding audiences at home, nevermind overseas.

"Such films don't bring many people into theaters," says Tsuchida. He adds that different communication styles between Japan and the West may further lessen the acceptance of Japanese films abroad.

Despite all this, both Ito and Tsuchida say that things have gotten much better and they remain optimistic. Directors like the late Juzo Itami and Masayuki Suo have recently presented modern Japan in a way that is accessible to foreign audiences. Suo's bittersweet romantic comedy Shall We Dance was one of the most successful foreign films ever in America.

Ito calls the work of both directors simplistic, but says they serve a purpose.

"They function as glue," he says. "They may present a very black-and-white image [of Japan], but Itami and Suo really work as a missing link between the samurai warriors and what's going on here now."

As for movies coming out of America, Ito cites the 1990 film, Come See the Paradise as proof that things are changing. Directed by Alan Parker, Come See the Paradise examines the U.S. government's internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II through the eyes of a G.I. (Dennis Quaid) whose wife (Tamlyn Tomita) and in-laws are sent to the camps.

"They couldn't have shown this kind of movie in the 1970s," says Ito.

Such changes are bound to continue, he says, as Asians continue to increase their collective profile and social status in America. If Hollywood's powers-that-be are unable to satisfy Asian needs, Asians will be able to support their own filmmakers.

Tsuchida agrees. "I feel positive about the future. There will be more movies in which more Asians appear and images of Japanese will be more true to life," he says.

Which brings us to the new millennium and Snow Falling on Cedars and Memoirs of A Geisha, two new high-profile movies with Japanese themes. Ito smiles at the irony that, despite the American film industry's increasing sophistication regarding Japan, one of the standby stereotypes, the geisha, is about to return -- as presented by an American writer. He considers it a necessary evil.

"For the business side, they [the studio] need the geisha. I don't know if people in America want to see a movie about Japan without a geisha," he says.

The geisha, he says, is a good hook. "The danger is that people will think these things are still going on here."

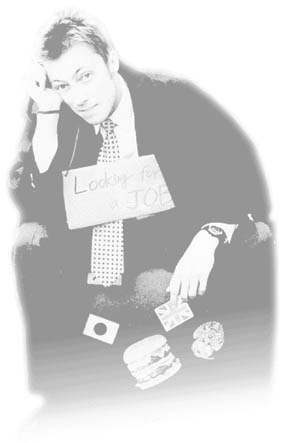

Hokkaido. Then What?

- Putting your experience to work back home - (Dec. 1999)

by Carey Paterson

For a foreigner in the good old days, a spell in exotic Japan was enough to make you a Japan expert. The mystery rubbed off on you, somehow, and businesses back home vied for your unique insight. Now, decades later, greater media attention has demystified Japan, and the strong yen has made it more common to find foreigners who have spent some time here.

If experience in Japan is no longer an automatic ticket to success, it still can be personally and professionally valuable, according to former residents of Hokkaido.

In the late '80s, Lynn Fredricks came to Japan in search of cash and adventure. He found both, and parleyed his seven years in Kyushu and Sapporo into a career in business development.

"Having gotten a head start on high-tech while in Japan proved to be a great asset," Fredricks says. "It isn't often enough just to gain a language skill, but also a cultural context and how it's applied to work. I've since worked at two major U.S. software companies managing their international business development."

MARKET YOURSELF

He is now president of Proactive International, a company that works with software developers to launch their products around the world. He says that marketing yourself is the key to leveraging your overseas background. "The perception of [your] experience in Japan depends on how you present it. My employers were very enthusiastic about my experience."

Now that he's on the other end of the resumˇ, he says Japan expertise can be an advantage, but is not inherently a plus.

"I judge Japan expertise like any other, as it relates to the task. About 50 percent of my company business relates to Japan, so what you did in Japan is extremely important, the type of work you've done, the number of jobs held, and your present knowledge and skill in dealing with Japanese business culture or language. More recent experience is more important because there have been some changes in business practices in Japan since the bubble burst.

"If the experience is over five years old and you haven't had any other experience, then I tend to not give it great value. I've known a number of people who come back and basically forget about their experience."

An international background is more commonplace than it used to be, Fredricks says, but there is still a demand for employees with such experience.

"When I returned, almost any [Japanese] experience was seen as an asset. For example, if your business experience in Japan was minimal, then you were often given ample room to 'ramp up' on it," he says. Unfortunately for the majority of foreigners in Hokkaido, Fredericks says teaching experience is of little use back home outside of the education field. The best experience is to be had working in a Japanese company, particularly in high tech. "I could use some of those [employees] in my organization," he says.

GONE TOO LONG

International workers seeking professional development can run the risk of staying away too long, as one mental health counselor learned after 12 years of teaching English in Hokkaido.

"My teachers [in the U.S.] thought my multi-cultural experience would make me very desirable to employers, but I was the last in my class to get a job," she says.

She also found herself out of touch with social trends and practices now taken for granted in her field. Her ignorance of confidentiality and the rights of parents versus those of children soon led to trouble.

"I made a mistake a few weeks ago that my supervisors said they had never imagined anyone would do, and they were shocked," she says, adding that her well-meaning attempts to protect a child had "unimaginable" repurcussions. The resulting uproar in her agency led to the departure of two supervisors who tried to protect her and has hampered her at work.

"They [management] worry that I'll make another serious legal mistake and have no clue what I did wrong. In their eyes I'm now a liability, and they don't know where to begin in training me," she says.

"The moral of the story is, if you want to return to the States to work, don't stay away too long."

Still, she says her time in Japan did make her more aware of the value of her own culture and the feeling of being discriminated against. "These were valuable lessons and are helpful in my current profession," she says.

If Japan is not as exotic as it once was, it still prompts some curiosity overseas, which can lead to opportunities.

"I found that everyone in the U.S.A. is intrigued and excited when I admit that I lived in Japan," says Pat Uskert, who is working in California as a film production assistant and boom operator. "They ask questions and want me to say something in Japanese. I wish that my Japanese was better...because I see so many ads in the Los Angeles Times seeking employees bilingual in Japanese. Damn! One more year, and I'm sure I would have it!"

Much as he once complained about teaching English in Japan, Uskert remembers his time in Hokkaido as idyllic -- after a bumpy start on Honshu.

"I'd just graduated from college and really had the desire to work in a foreign country. Japan sounded like a great idea. I'd studied two semesters of Japanese in college, and majored in English. It all fit together so perfectly that it had to be done!" His first school in Miyagi Prefecture "turned out to be a little dive, and the boss a genuine onibaba [witch]. She worked me like a slave." He had another false start in Sendai, where one school overtaxed him and another was "a dreadful scam of a place, cheating wonderful customers out of thousands of dollars and giving them poor English conversation from overworked teachers.

"I really think my love affair with Japan started the first day I landed in Sapporo to start a new life."

GAIJIN "GLASS CEILING"

One question returnees ask themselves is whether they want to work for a Japanese company in their home country.

Japan Travel Bureau interviewed Tim Callahan two months after he went back to New York. They snapped him up within 24 hours.

Callahan had spent two years on the Japan Exchange Teaching program in Nagasaki Prefecture and a year in Sapporo studying Japanese. He worked his Japan connections adroitly when he returned.

"A friend of mine who had been in Sapporo and returned to the New York area about six months before I did had compiled a list of employment agencies that had contacts at Japanese companies, of which there are a lot in New York City." This led him to JTB.

Although he has only good things to say about his former officemates, Callahan was put off by the banality of booking reservations for Japanese tourists and by the gaijin "glass ceiling."

"No gaijin had ever risen past supervisor," he says, "and the one guy who was a supervisor was a 'lifer' who had a Japanese spouse and had basically dedicated his life to preserving his link with Japan." Callahan left after two months.

He praises JTB for doing "a good job of importing the fun parts of Japanese business culture in the U.S., such as frequent enkais [parties]. Unfortunately the opposite is also true: long hours -- 8:30 a.m. to 6 p.m. -- and fairly poor pay.

"Although the people were all friendly and interesting, I got to use some of my Japanese, and I made some friendships that I still have, I soon realized that JTB was a dead-end job: travel itself may be fun and glamorous, but working in the travel industry is not."

He advises imminent returnees to evaluate their goals.

"I've found that most people who had a predominantly positive time in Japan but who don't have a definite career path start out going the 'Japan road' when they get back but then almost inevitably end up on the 'what I really want to do' road.

"My best advice for people who are leaving Japan and don't have a definite career path marked out is to think of themselves as starting from ground zero: The road lies entirely ahead of you, and you can do whatever you want. You're entirely free of baggage. Before rushing into anything, take some time to ponder what it really is you want to do and then start down that path. Don't be afraid to take chances, and don't feel obligated to do something Japan-related because you think it will somehow validate your decision to go there and commit a few years of your life to living there."